A sticky situation: FMNR in refugee camps

May 7, 2018

By Tony Rinaudo – World Vision Australia

Tony is currently conducting FMNR training in Uganda and his latest reflection piece shows how FMNR can be adapted to any situation, even refugee camps…

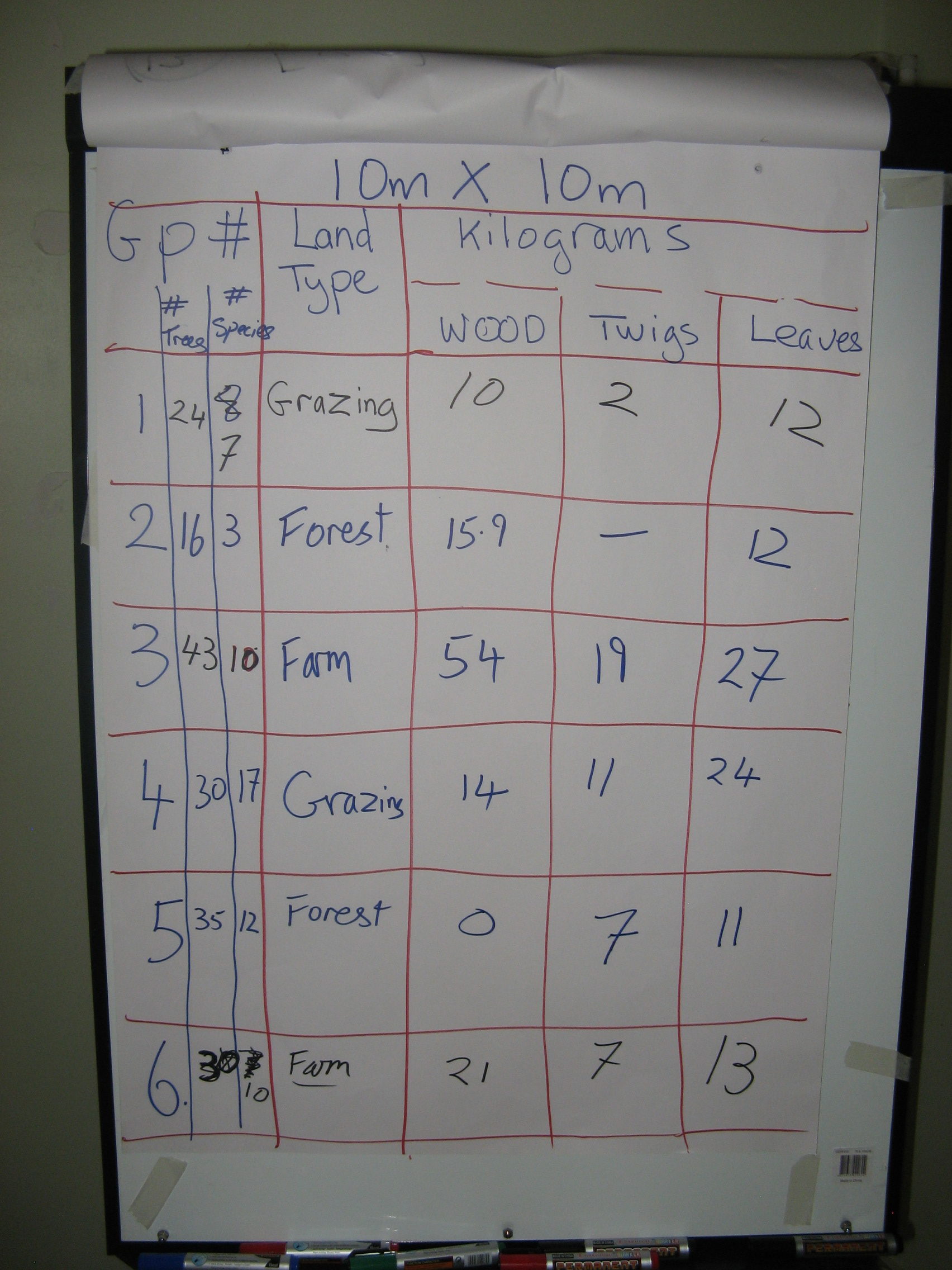

Because there is a particular emphasis on firewood in the refugee camps I did something I’ve never done before in a workshop, but I think I’ll make it a standard. I broke the participants up into groups of 5 members and instructed each group to select 10X10m area of land in a degraded forest full of stumps and bush encroachment. We counted the number of trees, no. of species and identified as many as we could, nominated what land use each group would be pruning for (cultivated land, grazing land, forest land), then weighed the firewood, twigs and leaves separately. I was interested in the twigs because they would normally be wasted – and left on the ground. Twigs can constitute a fire hazard – and fires are a serious issue and threat to success of FMNR and tree planting in Uganda and elsewhere. We can turn them into charcoal briquettes – helping income needs, or helping meet a critical fuel shortage. The briquettes are a unique unmistakable shape, so can easily be distinguished from charcoal derived from destroying trees.

The leaves would normally be left on the field – and still can be, but I also wanted a measure of this to determine quantities available for composting. And counting the fuel wood is self-explanatory. Composting is important – we have 1,000,000 plus resource poor South Sudanese settlers depleting the soil and making it prone to erosion through their farming methods – the same is true also for Ugandan farmers. What a gain if we could capture this otherwise lost resource and turn it into fertilizer!

As it turned out, most of the participants also really valued the weighing and measuring exercise. There was great scepticism that the landscape could provide sufficient fuelwood to meet energy needs, while still regenerating the forest. After the exercise they were much more positive. The fact that the site we worked on was less vegetated than many of the bush encroachment areas in the settlement made us all wonder just how much wood is out there ready to be harvested in the process of improving the environment?

Normally in workshops in the past, more than half the participants barely even put their hand to trying FMNR. But this time, because I broke them into small groups, and they had a definite target – treat 10mx10m, everybody had a turn. I think there was a competitive spirit amongst each group – not wanting to be shown up by the others!

The other thing I changed was to begin with a practical demonstration, following a very brief introduction to FMNR with slides. Normally the practical falls in the afternoon or on the next day of a workshop. However, most people really don’t know what I’m talking about until they see with their own eyes and physically do it. The lights really do come on in the field. Additionally, whereas most have a negative attitude, thinking that farmers will not adopt FMNR or tolerate trees on farms, they were convinced by the interest shown by passers by. They realised that it would not be such an insurmountable task. I had a similar experience with a well-educated, commercial farmer in Rwanda the previous week – he had done everything in his power to remove “useless native trees” from his land. I asked permission to just demonstrate FMNR in a small area on his grazing land. He agreed. Before I finished pruning the very first bush he said “I got it”. Puzzled, (because he had been pushing back strongly about why he should carry the cost of saving native trees) I asked “what did you get”?

He replied that he could see already that firstly, by pruning in this way the trees would stop spreading and taking up more land by suckering, and that secondly, there would now be more light hitting the ground at the base of the tree, allowing grasses to grow!