The spread of FMNR in Niger

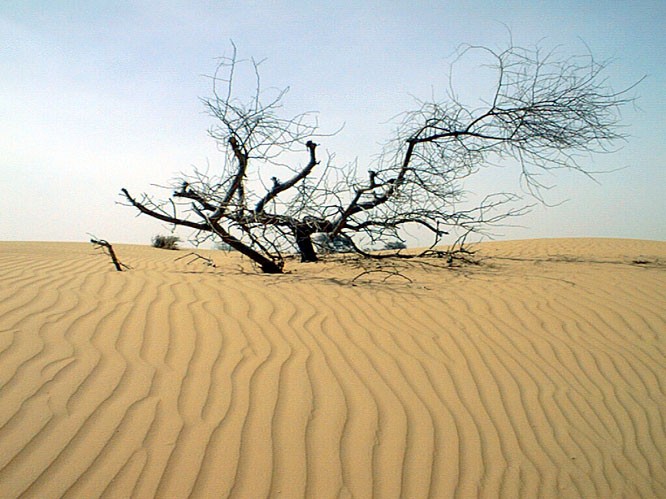

The almost total destruction of trees and shrubs in the agricultural zone of Niger between the 1950s and 1980s had devastating consequences. Deforestation worsened the impact of recurring drought, strong winds, high temperatures, infertile soils, pests and diseases on crops and livestock. Combined with rapid population growth and poverty, these problems contributed to chronic hunger and periodic acute famine.

In 1981, the whole country was in a state of severe environmental degradation; an already harsh land was turning to desert, and people were under severe stress. More and more time was spent gathering poor quality firewood and building materials. Women were required to walk for miles to collect small branches and millet stalks, and even cattle and goat manure was used as fuel. This further reduced the fodder available for livestock and manure available for use as fertiliser. Under the cover of dark, people would dig up the roots of the few remaining protected trees.

Without protection from trees, crops were hit by 60-70 km/hour winds and were stressed by higher temperatures and lower humidity. Sand blasting and burial during wind storms also damaged crops. Farmers often needed to replant crops up to eight times in a single season. Insect attack on crops was extreme and natural pest predators had disappeared along with the trees.

Conventional approaches to reforestation through raising tree seedlings in nurseries and planting them out were a failure.

Acceptance of Farmer Managed Natural Regeneration (FMNR) was initially slow. A few people tried it but were ridiculed. Trees protected through FMNR were often cut and stolen. A change in mindset began in 1984, following intense radio coverage on deforestation in the Maradi region of the country. This was followed by a country-wide severe drought and famine, which reinforced this link in peoples’ minds. During the famine and through a food-for-work program, communities were required to practise FMNR on their farmland. For the first time, people in a whole district were leaving trees on their farms. Some 500,000 trees were protected. Many people were surprised that their crops grew better amongst the trees. All benefited from having extra wood for home use and for sale.

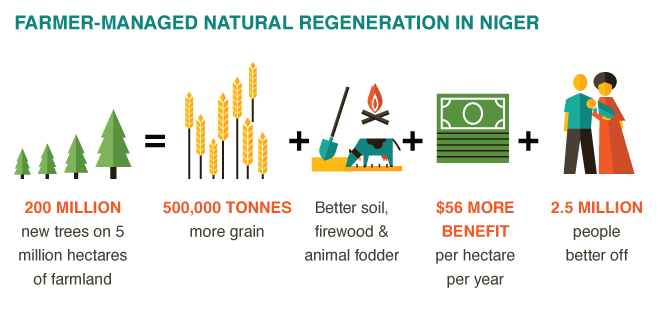

Sadly, once the food-for-work program ended, over two-thirds of the trees were chopped down! However, district-wide exposure to the benefits of FMNR over a 12-month period was sufficient to introduce the concept and reduce fears about growing trees with crops. Gradually more farmers started protecting trees again until FMNR became a standard practice. Over a 20 year period, this new approach spread largely from farmer to farmer, and today five million hectares of farmland have been re-vegetated. This significant achievement occurred in one of the world’s poorest countries with little investment in the forestry sector by either the government or NGOs. FMNR rapidly moved from being a “project” to becoming a “movement”.

Typical farm scene before FMNR introduction.

Farmers believed that a good farmer was a “clean” farmer who would cut down all farm trees and sweep up and burn any crop residue and organic matter on the farm. As trees belonged to the government, there was no incentive for farmers to protect them from thieves. Theft of trees was common, and many farmers chose to cut down the trees on their land themselves, so that they would at least benefit from the wood.

Typical farm scene after FMNR introduction.

Today, farmers are leaving an average of 40 trees per hectare and some are leaving as many as 150 trees per hectare – on their farmland. They benefit from increased income from the trees, improved crop yields and increased supply of fodder for livestock. Wind speeds have reduced and in some regions, water tables have risen.

Key elements contributing to the rapid spread of FMNR in Niger and lessons learned:

- Convincing a large percentage of the community of the value of FMNR facilitated rapid uptake. District-wide promotion of FMNR resulted in a critical mass of people being engaged in the same activity.

- Farmers need assurance that they will benefit from their efforts. By working with the forestry department, an enabling environment was created in which farmers believed that they would benefit from their labour on FMNR.

- Regular follow-up by trusted staff and farmer FMNR champions, and teaching by example, are very important. Project staff and FMNR farmer champions lived in the villages and were required to practise FMNR on their own farms, thus teaching by example.

- Early (within the first year), direct rewards from FMNR such as firewood from pruned branches, increased income from sale of wood, reduced erosion, reduced wind speeds, increased fodder availability and increased crop yields act as powerful incentives for adoption and encourage farmers to practise FMNR even more intensively.

- The main means of spreading FMNR was farmers themselves – outside of project interventions. As farmers benefited, they began sharing their knowledge with other farmers independently of the project.

- Sharing knowledge is critical to generating an FMNR mass adoption or movement and therefore having an impact at scale. Entrusting training to farmers themselves is very empowering. The project provided training and hosted exchange visits by external farmers’ groups, other NGOs, government agricultural and forestry extension services, farmer and church groups. Project staff and FMNR farmer champions were also sent to other regions of Niger where communities were requesting teaching.

Some of the many challenges included:

- Traditional practices: The tradition of free access to trees on anybody’s property and a code of silence protecting those who cut down trees had to be overcome. This situation was successfully addressed through advocacy, creation of local bylaws, and support from forestry agents and village and district chiefs in administering justice.

- Beliefs: Fear that trees in fields would reduce yields of food crops. Field results and measurements showing that crop yields actually increased eliminated these fears over time.

- Inappropriate government laws: If the farmer does not have the right to harvest the trees he has protected, there will be little incentive to do so. By collaborating with the forestry service, agreement was reached that if farmers practised FMNR they would be allowed to legally harvest and sell wood.

- Food-for-work during famine was an effective means of introducing FMNR on a district-wide basis, however,

- once crops were harvested, the food-for-work program was discontinued.

Benefits of FMNR in Niger

- Increased volumes of firewood on-farm: This saves hours of time, especially for women and children. Farmers save money by now producing their own wood, and diversify and increase income through the sale of wood.

- Increased soil organic matter and fertility: Tree roots absorb nutrients from deep in the soil and convert

- them to soil organic matter via leaf and fruit drop. Leguminous trees increase soil nitrogen. The presence of trees reduces erosion and evaporation and attracts animals which graze and deposit manure and urine onto the soil.

- Increased productivity of livestock: Animal fodder in the form of tree leaves and seed pods became available, reducing livestock mortality and increasing productivity.

- Improved pest control: Trees attract toads, lizards, birds and spiders which prey on crop-eating insects.

- Increased nutritious food: Indigenous trees provide edible fruit, seeds and leaves. Honey production also

- became possible.

- Diversified production for diversified incomes: Trees provide saleable food, medicinal products and timber.

- Usually, such products are available or in season when conventional agriculture is out-of-season, allowing activity and incomes to be spread across the year.

- Desertification was halted and deforestation was reversed.

- Biodiversity increased.

- Water tables rose in some regions.

- Disaster resilience increased as people now had reserves (standing trees) to draw on.

- Conflict over scarce resources reduced.